This page introduces you to some of the principles of flight, how gliders launch and stay airborne and how we land them again safely. You do not need to know everything that is explained here for your first visit, however if you are extra keen or want to impress your instructor read on.

Theory of Flight

When people first learn that gliders don’t have an engine, they often ask “so how does it stay up?” It is a common misconception that an aircraft, be it an airliner like a 747 or a small light aircraft requires an engine (thrust) to stay airborne. This is simply not true, in fact when designing a new aircraft, aircraft manufacturers have to design it so that they can glide for a certain distance without any engines working at all.

The diagram above shows the forces acting on a powered plane and a glider in flight. The lift produced by a glider acts in a direction angled slightly forwards, providing a force to counter the drag produced.

Controlling a Glider

The attitude (how far up or down the nose points) and therefore speed of the glider is controlled by the elevator, which is the control surface on the horizontal tailplane. This is controlled by the forward and backward movement of the control stick in the cockpit. Pushing the control stick forward moves the elevator downwards, lifting the tail and lowering the nose. This will increase the speed. Pulling back on the stick does the reverse, pointing the nose upwards and slows the glider down.

Just like a powered aircraft, gliders can be turned in the air with the ailerons, which are the control surface on each of the wings. Moving the control stick to the left raises the right wing and lowers the left wing, rolling the glider to the left. Moving the stick to the right does the opposite, and rolls the glider right.

The last primary control is the rudder, controlled by the pilot’s feet. The rudder changes the direction that the glider is pointing on the vertical axis, called the yaw. Turning is achieved with the ailerons and rudder being used in combination with each other.

Launching

Being un-powered, gliders need to get airborne somehow. There are 2 main launching methods we use, and some other methods that are used at other sites, which we may visit on an expedition.

Winch Launching

Perhaps the most common method of launching gliders is by winch launch. The idea is that at the opposite end of the airfield, there is a large winch, with a cable running all the way back along the field to the glider. The winch has a very powerful engine, capable of accelerating the glider from a standing start to 60mph in as little as 2 seconds! The glider’s wings start producing lift, and the pilot can then point the glider upwards at a 45 degree angle, rapidly gaining height. A winch launch can get you to 1,000ft in as little as 10 seconds on some days. There isn’t much in the world that will do this quicker on the right day, not even the Space Shuttle!

After a launch to typically about 1,300ft (but sometimes over 2,000ft when it is windy), the pilot releases the cable and continues the flight from there, hopefully catching a thermal to gain even more height.

Winch launches are popular because they are cheap, quick and can achieve a high launch rate if operated efficiently.

Aerotowing

Gliders are also commonly launched by aerotow. The glider is attached to a powered aircraft with a rope, the powered aircraft then takes off and climbs, dragging the glider along with it. Once the glider is at an altitude and position they are happy with, they simply release the rope and fly away, the aeroplane (called the “tug”) then returns to the airfield ready to collect the next customer.

The advantage of aerotowing is that it allows the pilot to choose where they get dropped off (for example, under a nice thermal!), and at what height the launch is taken to. They are more expensive than winch launches, and have a slower launch rate. Using several tow planes at once can achieve a good launch rate though, with most competitions using this launch method.

Other Launching Methods

Some other launching methods you might come across are:

- Auto tow – The glider is attached to a car by a length of rope, which then drives down the runway, giving the glider air speed and allowing it to fly

- Self Launching – This one applies to motor-gliders, and is fairly self-explanatory – the motor glider launches using its own propeller to give it air speed

- Bungee – The glider is pulled down a hill with the aid of a bungee rope, until it has enough speed to fly. The bungee rope is then released, leaving the glider to fly

Staying Airborne

So you’ve just launched a glider off a hill, you might be wondering whether you have to go and collect it from the bottom of the hill to have another go? Luckily, there are ways for gliders to stay airborne for hours, or more in a lot of cases. The atmosphere around us is never stationary, air moves both horizontally (as wind) and vertically. If we can position the glider in the upwards moving air, and the air is moving upwards faster than the glider is sinking downwards, we can gain height. Think of it as a person trying to walk down a fast escalator: if the escalator is moving fast enough, the person will be taken upwards, despite the fact that they are walking down it.

There are 3 basic types of lift that gliders use to stay airborne…

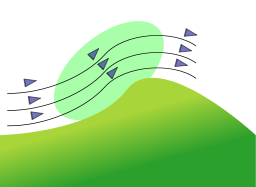

Ridge Lift

Ridge lift is the easiest to imagine – the wind blows against the face of a hill (or a cliff), and the hill deflects the air upwards. The glider can fly in this upward moving air to gain height or stay at the same height. The closer to the hill you are, the stronger the lift will be. Even light winds of around 10 mph can be enough to keep a glider airborne, depending on the hill and the skill of the pilot.

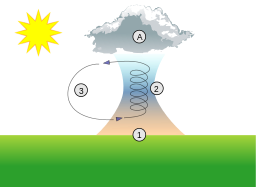

Thermals

In the summer (or even in spring and autumn when the sun is shining) different areas of the ground will heat up in the sun faster than others (for example, dark fields). These warmer areas heat up the air around them, and this air eventually breaks away from the ground as a bubble of warmer, rising air. These are called thermals, and gliders can use them to gain height on good days. Since they are roughly cylindrical in shape, gliders will turn in reasonably tight circles in order to stay in them. On a summer’s day, you can often see gliders turning in circles inside thermals to gain height.

As the air rises, it cools down, and eventually it will reach a height where the water vapour inside the air will condense, and form a cumulus cloud. These are the clouds that glider pilots look for in order to find where the thermals are located. The white, fluffy clouds you see on a summer’s day are all indicators that there is a thermal underneath them.

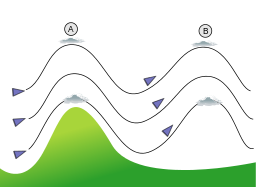

Wave

When a strong wind blows across a series of obstacles, such as a range of hills or mountains, the air will flow up one of the obstacles and down the other side (just like in ridge lift). This process gets repeated throughout the mountain range which causes the air to continue oscillating well beyond the mountains and upwards of tens of thousands of feet.

Many height records have been set in wave, up to the heights commercial airliners fly at, and sometimes even higher. The world record for height in a glider stands at over 50,000ft. Pretty impressive for something that is only using the natural currents in the atmosphere to gain height!

We occasionally get wave at Cranwell on a strong wind day, but the best places to look for wave without leaving the UK is Scotland, Northern England and Wales. We organise an expedition to Portmoak in Scotland every year to try and sample some of these unique conditions!

Landing

Eventually of course, you are going to want to land. Since gliders are so efficient, it is actually harder than you think to get them to come down! A typical training glider will travel about 30-35ft forwards for every foot in height it loses – equivalent to a glide angle of less than 2 degrees. For this reason, most gliders are fitted with airbrakes which help to destroy some of the lift and allow the glider to descend at a faster rate. The amount of airbrake used will effect how steep the approach is and how quickly the aircraft descends. The pilot can therefore use them to pretty much land the glider exactly where they want.

The final phase of the landing is the “round out” or the “flare”. This involves gently pitching the aircraft upwards just before it touches down in order to reduce the vertical speed and make for a nice smooth touch down. At first, you may find this very challenging to get right, however over time you will naturally get a feel for how to handle the aircraft in this last phase of flight.

Summary

Hopefully this page has given you basic information on how a glider is launched, how it is controlled and how it can stay airborne. There is a lot more to it all than what has been covered here, but it is all easily picked up as you learn to fly with us. It isn’t essential that you know everything here when you come to the airfield for the first time, but understanding the concepts is a good start and will enable you to learn the more advanced theories easily.